Lorely Miller said she owes her life to the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Oregon State University. “I do not believe that I would still be alive today.”

Miller contracted tularemia, an extremely dangerous, highly contagious bacterial disease. People usually get tularemia from other animals. In her case, from a squirrel.

On May 2, 2018, while leaving her home, a squirrel ran up to her as she stepped off the front porch. The animal seemed distressed — perhaps injured. Being an animal lover, she tried to help the squirrel but it bit her finger before she corralled it in a box.

An hour later the animal was dead.

Acting on intuition, Miller did something she’d never done before: she put the dead squirrel in a Tupperware and put it in her freezer.

“I’ve never frozen an animal body in my life,” she said.

This decision would prove pivotal to her health.

A week after the squirrel died, Miller fell gravely ill. She developed a variety of maladies including fever, profuse sweating and boils. A particularly large one developed behind her ear.

She knew it had something to do with that squirrel, but she didn’t know how. After being frustrated by doctors at the hospital not taking her illness seriously, the county public health office recommended she take the squirrel to the OVDL.

The Case Gets Squirrely

Miller delivered the squirrel’s body to the OVDL hoping she’d learn something to help her understand her ongoing medical troubles. Unknowingly, she and the squirrel were about to enter the network of individuals and institutions in Oregon and beyond working every day behind the scenes to stamp out potentially dangerous zoonotic diseases in the name of public health.

A necropsy (animal autopsy) was overseen by Dr. Christiane Löhr, a pathologist with 20 years experience at the OVDL. Löhr knows to beware when dealing with Oregon squirrels. They have a reputation for potentially harboring two notorious, dangerous bacteria: Yersinia pestis — the plague known for killing upwards of 25 million people in the 14th century and Francisella tularensis, the cause of tularemia.

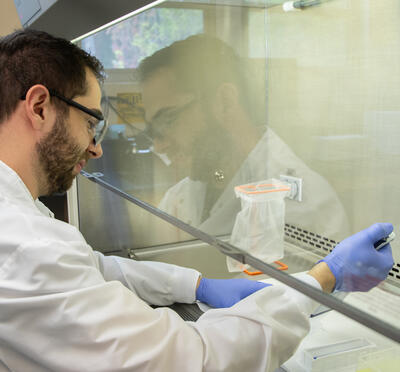

Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory bacteriologist Sophia Ballard works with Francisella tularensis in a biological safety cabinet. (Courtesy: Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Oregon State University)

The body was worked on in the confined space of a biological safety cabinet which controls airflow, preventing human exposure during the process. At this stage, nothing suspicious was seen indicating an infection in the squirrel.

One look at the squirrel’s liver and spleen under the microscope changed Löhr’s tune. Both organs were wiped out, and copious bacteria were found.

“After seeing this we were very concerned about plague and tularemia,” Löhr said.

These findings represented a giant step forward in potentially explaining Miller’s health troubles. Löhr then set to work identifying the bacteria. To do this, a sample of spleen from the squirrel was sent to the OVDL’s bacteriology laboratory.

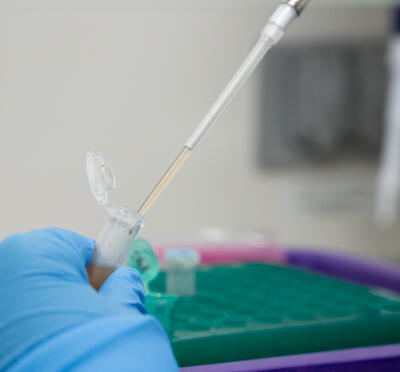

A swab was plunged into the spleen and streaked out on the surface of three different types of agarose plates (blood, MacConkey and chocolate). Each of the three plates chosen offers something different to bacteria, making them useful for distinguishing bacteria from one another.

Several days later: eureka. Small, pearlescent, buttery colonies peppered the surface of the chocolate agar, suggesting F. tularensis.

Sophia Ballard, a bacteriologist at the lab, and her colleagues needed more information to be sure. They performed two more tests and felt comfortable making the call.

Colonies of Francisella tularensis isolated by bacteriologists at the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory growing on a chocolate agar plate. (Courtesy: Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Oregon State University)

Even before Miller, they called Rob Nickla, at the time the Laboratory Response Network (LRN) coordinator for Oregon. He was called because of the bacteria’s nature: it’s a select agent.

“This isolate is very pathogenic; it’s the definition of a select agent” Ballard said.

The Federal Select Agent Program was created in 2001 following the anthrax attacks that killed five people and hospitalized 17 in the most serious act of bioterrorism in U.S. history.

Tularemia is on that list, along with dozens of other bacteria, viruses and toxins that pose significant threat to public health, animal health and the health of U.S. agriculture.

Because of the significance of select agents, there’s a hierarchy of people and agencies that must be contacted to assist impacted people, like Miller, and to be sure the whereabouts of the select agent is followed and properly handled to prevent it from falling into the wrong hands.

For Nickla, the case illustrates the importance of the LRN.

“The LRN was formed in 1999 and got a huge boost in 2001 following the anthrax attacks. The program is really designed to have preparedness and response capabilities for emerging threats,” he said.

He describes the LRN as a “three-tiered pyramid.” At the top of the pyramid is the CDC, which controls protocols and assays used by laboratories in the lower two tiers. His former employer, the Oregon State Public Health Laboratory, is the state’s reference laboratory, placing it in the middle tier. The base of the pyramid is comprised of dozens of sentinel laboratories in Oregon: the first line of defense in the detection of select agents.

The Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory is one of the most important sentinel laboratories in the state.

“The OVDL sees more select agents than all the other hospitals combined,” Nickla said. “The mantra for the LRN is, ‘recognize, rule out and refer.’”

The OVDL recognized the bacteria recovered as potentially F. tularensis; they ruled out other potential mimics and then referred the case and bacteria up the pyramid to the OSPHL. There, Nickla’s former colleagues confirmed the bacteria as F. tularensis and referred the case to the CDC.

Miller was told the news about the squirrel’s diagnosis from Dr. Mark Ackermann, former director of the OVDL. He called Miller to update her on what was found in the squirrel, imploring her to see a physician.

Being potentially infected with a select agent moved Miller to the top of the LRN pyramid. A blood test for tularemia administered by the CDC finally gave her a diagnosis.

It was a very emotional moment for Miller.

“I tested positive for tularemia, that’s when I cried for joy,” she said.