Circling Back to the Kidneys

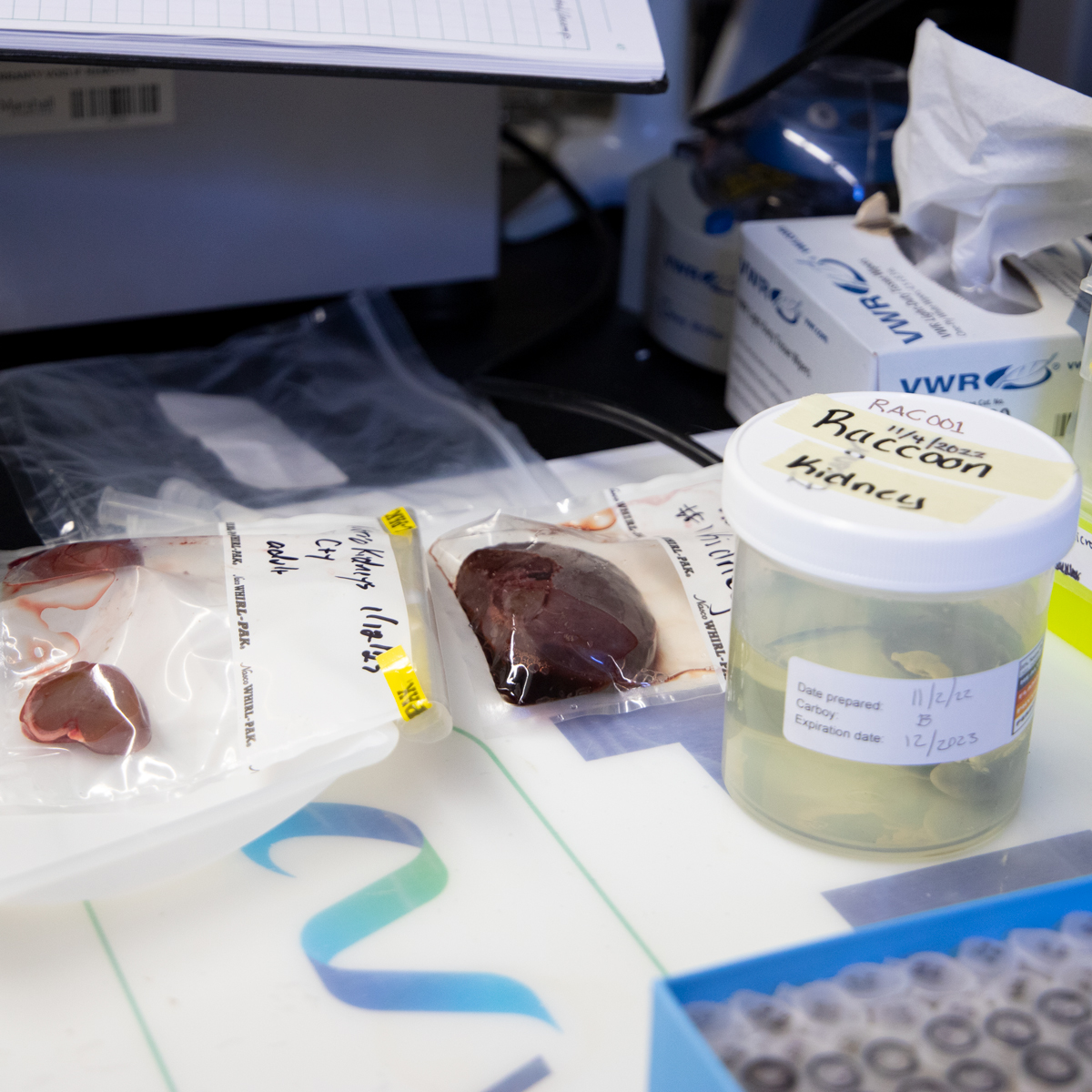

It’s not just squirrel and beaver kidneys that Hayes is processing. She's looking for leptospirosis in all kinds of wildlife from across the state of Oregon. We’re talking rats, porcupines, nutria, chipmunks, voles, opossums, “a marmot,” skunks and raccoons. “I have a freezer full of kidneys I need to go through,” she said. “This was a doozy of a semester.” The freezer is housed in a research laboratory in the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Oregon State University’s Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine.

Hayes gets the deceased animals from a variety of wildlife agencies and organizations across Oregon like the Chintimini Wildlife Center in Corvallis, Think Wild in Bend and the United States Department of Agriculture to name a few. They’re animals that were brought in sick to rescue organizations and died, were collected as roadkill or were found dead in the field.

“I reached out to the wildlife rehab places because if someone notices a sick animal, they're going to bring it to those guys. And if the animal recovers, that's great. But if the animal was so sick that it's succumbed, there's often not spare money to test what caused the mortality,” Hayes said. “So me reaching out and getting these carcasses is actually answering questions that the rehab places have had, but don't have the funds to really research.”

The deceased animals are necropsied by the anatomical pathologists at the college’s Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. “We take a small sample of kidney, not much more than a few grams,” said Dr. Duncan Russell, associate professor of anatomic pathology. Samples are taken from this organ because “the bacteria hide in the renal tubules in the kidney,” Hayes said.

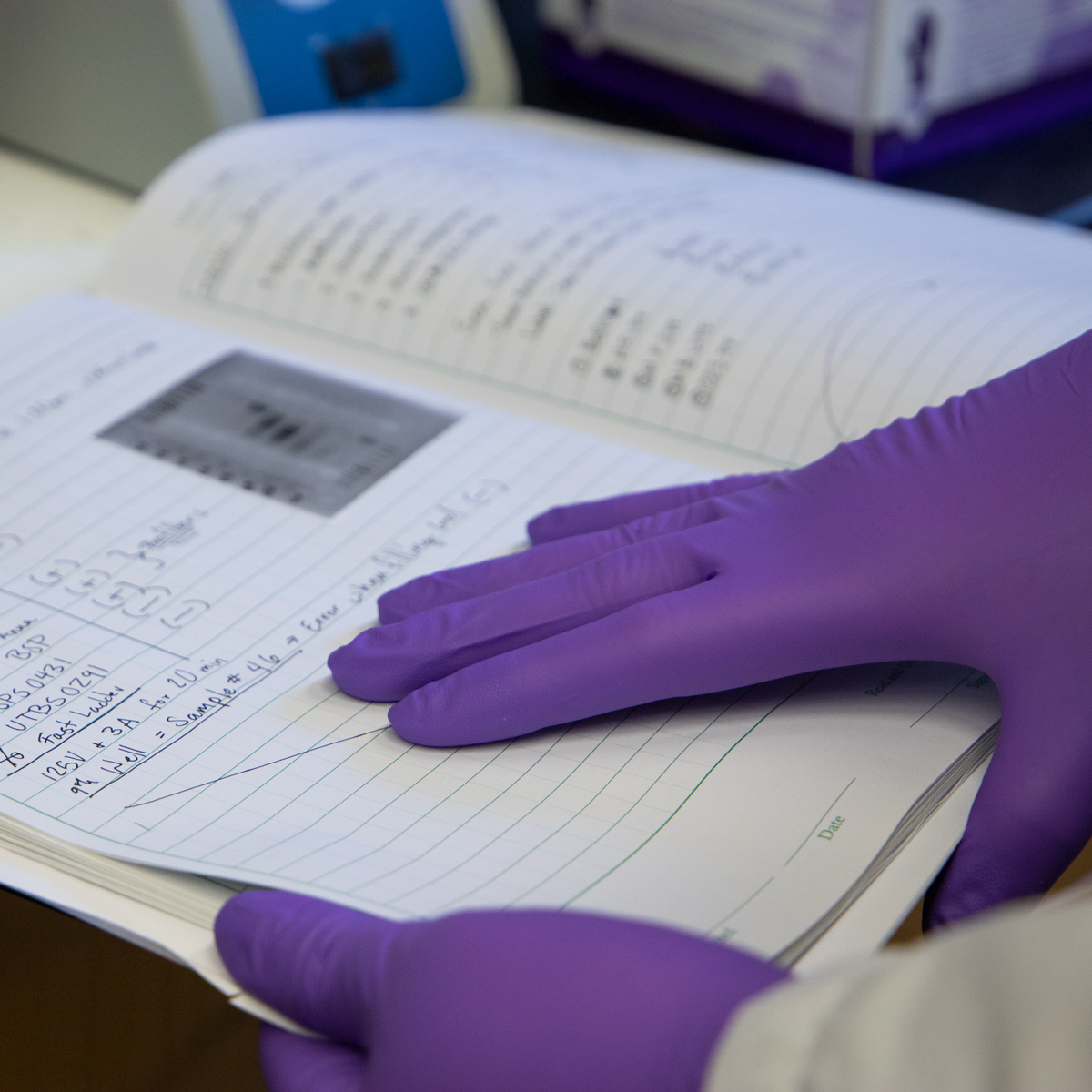

The samples are then tested for the disease and, if detected, run through further analysis.

“Basically, I’m getting more strings of DNA that are from different parts of the DNA strand that can tell me how different things are,” Hayes said. With each kidney sample, Hayes is able to get a clearer picture of what species of wild animals are carrying the organism and the specific genetic makeup of the bacterial strain they are infected by.

As more and more samples are processed, the idea is that she’ll be able to start identifying “reservoir species” of wild animals that carry the organism. In the scientific community, a reservoir species means one that the organism thrives in naturally and which, like a reservoir of water, supplies other species who come in contact with it with the bacteria.