Editor's Note: This story was first published in Nov. 2023.

Story by Dr. Kurt Williams. Photos by Jens Odegaard

Baker County in eastern Oregon has a mosquito problem.

“We get plenty of mosquitoes, that’s for sure,” said Matt Hutchinson, manager of the Baker Valley Vector Control District (BVVCD), in Baker City, Oregon.

Mosquitoes in the valley, as most anywhere, can be a nuisance. But some may also transmit potentially dangerous viruses, such as West Nile virus, threatening the health of the region’s people and horses.

To monitor the potential threat, Hutchinson teams up with scientists at the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (OVDL) at Oregon State University to keep tabs on viruses in local mosquitoes (watch the team in action).

“Right about the end of July was our first positive West Nile test this year,” he said.

Data compiled by the Oregon Health Authority shows Baker County leading the state in detection of West Nile virus in mosquitoes, with three Baker County residents having been diagnosed with the disease. Other eastern Oregon counties, including Morrow, Umatilla, Union, Malheur and Harney also had West Nile virus detections in mosquitoes this year, with an additional seven cases of infection in people scattered around the state.

Cattle in Baker County graze in flood-irrigated pasture.

Just Add Water

In high summer, the Baker Valley is bucolic. Tens of thousands of lush acres stand in stark contrast to the dun-colored Elkhorn and Wallowa mountains encircling the valley. The valley’s verdancy and mosquito problem don’t happen without water – lots of it.

“There’s just a ton of flood irrigation in this valley,” Hutchinson said.

In 1968, Mason Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation, backing up the Powder River that runs through the Baker Valley, forming Phillips Reservoir to provide flood control and more reliable water for flood irrigation in the valley throughout summer.

Mosquitoes, finding flooded pastures conducive to reproducing, exploded in numbers. Following the completion of the dam, their aerial assault on the region’s cattle got so bad the animals spent more time avoiding mosquitoes than eating, leading to decreased weight gain.

In November 1975, the county mosquito control district was officially created by voters to address the problem. But changes would soon impact the citizens of Baker County, Hutchinson, and the OVDL.

West Nile virus, first documented in Uganda in 1937, circulated for decades in Africa and parts of Europe as a mild disease. In the mid-1990s, a new more serious variant of the virus arose, causing neurologic disease.

The virus was detected in New York state in the late 1990s, likely arriving in an infected person from the endemic region. Local mosquitoes picked up the virus where it went on to infect and kill many wild birds, along with a number of horses and humans. By 2012, West Nile virus was found in all 48 states of the continental United States.

Because of this, Hutchinson’s summers in Baker County are now spent in a way his predecessors in the 1970s couldn’t imagine: collecting mosquitoes to send to the OVDL.

“We usually start trapping mosquitoes the first week of June, and it runs to the middle or end of September,” he said.

During mosquito season Hutchinson and his team set traps weekly in 36 locations across the district. Traps are set in the late afternoon and collected the following morning. Looking a bit like a windsock on a windless day, traps are hung low from trees or poles below canisters containing the bait: dry ice. Carbon dioxide sublimating from the ice mimics the breath of mammals and birds mosquitoes find irresistible. When they come in to investigate, a fan blows them into the trap to await collection.

Trapped mosquitoes brought back to the BVVCD lab are counted, identified, sorted and frozen for shipment to the OVDL. For each site collected, Hutchinson enters the number of mosquitoes, collection date and species of mosquito into a database.

Test results returned to Hutchinson from the OVDL are linked to trap location, allowing him to make decisions regarding potential interventions. He also communicates findings with the public.

“Whenever we get a positive test result from the OVDL, we prepare a press release and push it out through our social media and local media sources to keep the public informed.”

“I think when West Nile started to break in the 1990s is when we became more focused on public health,” Hutchinson said.

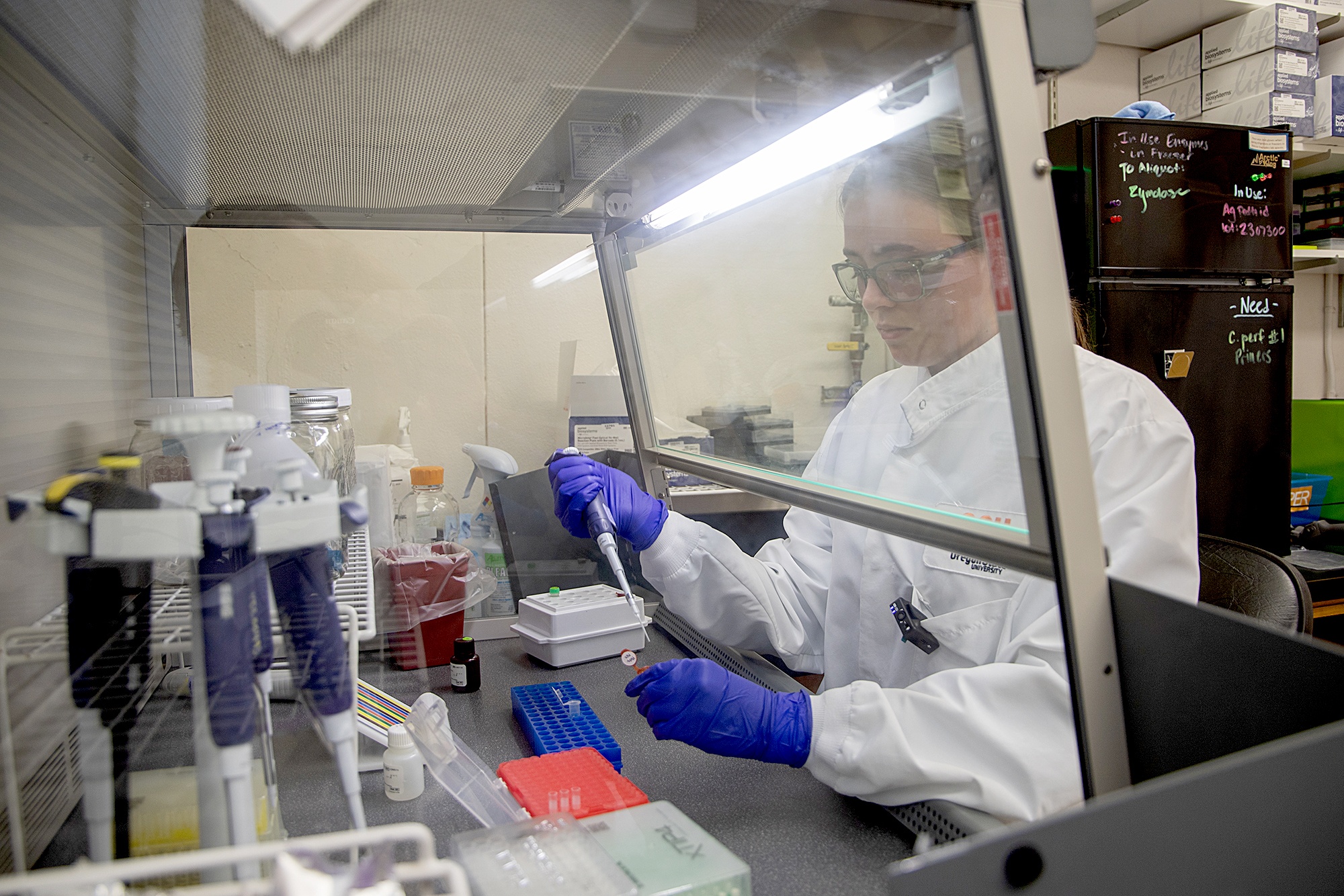

Ella Reese at the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory prepares mosquitoes to test for viruses that can infect people.

West Nile virus, first documented in Uganda in 1937, circulated for decades in Africa and parts of Europe as a mild disease. In the mid-1990s, a new more serious variant of the virus arose, causing neurologic disease.

The virus was detected in New York state in the late 1990s, likely arriving in an infected person from the endemic region. Local mosquitoes picked up the virus where it went on to infect and kill many wild birds, along with a number of horses and humans. By 2012, West Nile virus was found in all 48 states of the continental United States.

Because of this, Hutchinson’s summers in Baker County are now spent in a way his predecessors in the 1970s couldn’t imagine: collecting mosquitoes to send to the OVDL.

“We usually start trapping mosquitoes the first week of June, and it runs to the middle or end of September,” he said.

During mosquito season Hutchinson and his team set traps weekly in 36 locations across the district. Traps are set in the late afternoon and collected the following morning. Looking a bit like a windsock on a windless day, traps are hung low from trees or poles below canisters containing the bait: dry ice. Carbon dioxide sublimating from the ice mimics the breath of mammals and birds mosquitoes find irresistible. When they come in to investigate, a fan blows them into the trap to await collection.

Trapped mosquitoes brought back to the BVVCD lab are counted, identified, sorted and frozen for shipment to the OVDL. For each site collected, Hutchinson enters the number of mosquitoes, collection date and species of mosquito into a database.

Test results returned to Hutchinson from the OVDL are linked to trap location, allowing him to make decisions regarding potential interventions. He also communicates findings with the public.

“Whenever we get a positive test result from the OVDL, we prepare a press release and push it out through our social media and local media sources to keep the public informed.”

Matt Hutchinson from the Baker County Vector Control District identifies, and sorts trapped mosquitoes before shipping to the OVDL for testing.

Bugs in the System

Mosquitoes arrive at the OVDL via overnight delivery to the laboratory’s Receiving section. Katrina Voll supervises the busy department that receives anywhere from 70 to 100 cases every day that may contain one to dozens of individual samples needing testing. Everything from feces tested for parasites and whole animals for necropsy to mosquitoes.

In 2023, ten Oregon county vector control agencies – Baker, Columbia, Klamath, Lane, Malheur, Morrow, Multnomah, Umatilla, Union and Washington, along Grant County in Washington State, submitted mosquitoes to the OVDL for testing. The laboratory performs PCR testing for three viruses potentially dangerous to humans: West Nile, St. Louis encephalitis and western equine encephalitis virus. This year, over 78,500 mosquitoes were trapped and submitted to the OVDL for testing. The laboratory performed over 2,700 PCR runs on the submitted insects, with 90 samples positive for West Nile virus. Baker County leads the state with 29 positives.

The future of vector borne diseases in Oregon and elsewhere will surely change, presenting new threats to the health of Oregonians, and challenges for the OVDL. A warming climate is resulting in longer mosquito seasons in northern states of the United States, favoring the expansion of mosquito and tick-borne diseases. Dengue, a devastating viral disease transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, is identified by the World Health Organization as a growing threat in the Americas.

Kenny Carver, Mosquito Control Coordinator for Washington County, Oregon, served as past president of the Oregon Mosquito Group. He’s concerned about what the future may bring. Right now, we don’t have A. aegypti and A. albopictus established in Oregon.

“As climate change takes place and then the environment changes, mosquitoes expand; the potential is there, and we’re seeing that with A. aegypti. They’re moving farther north in California, getting closer to our border,” Carver said.