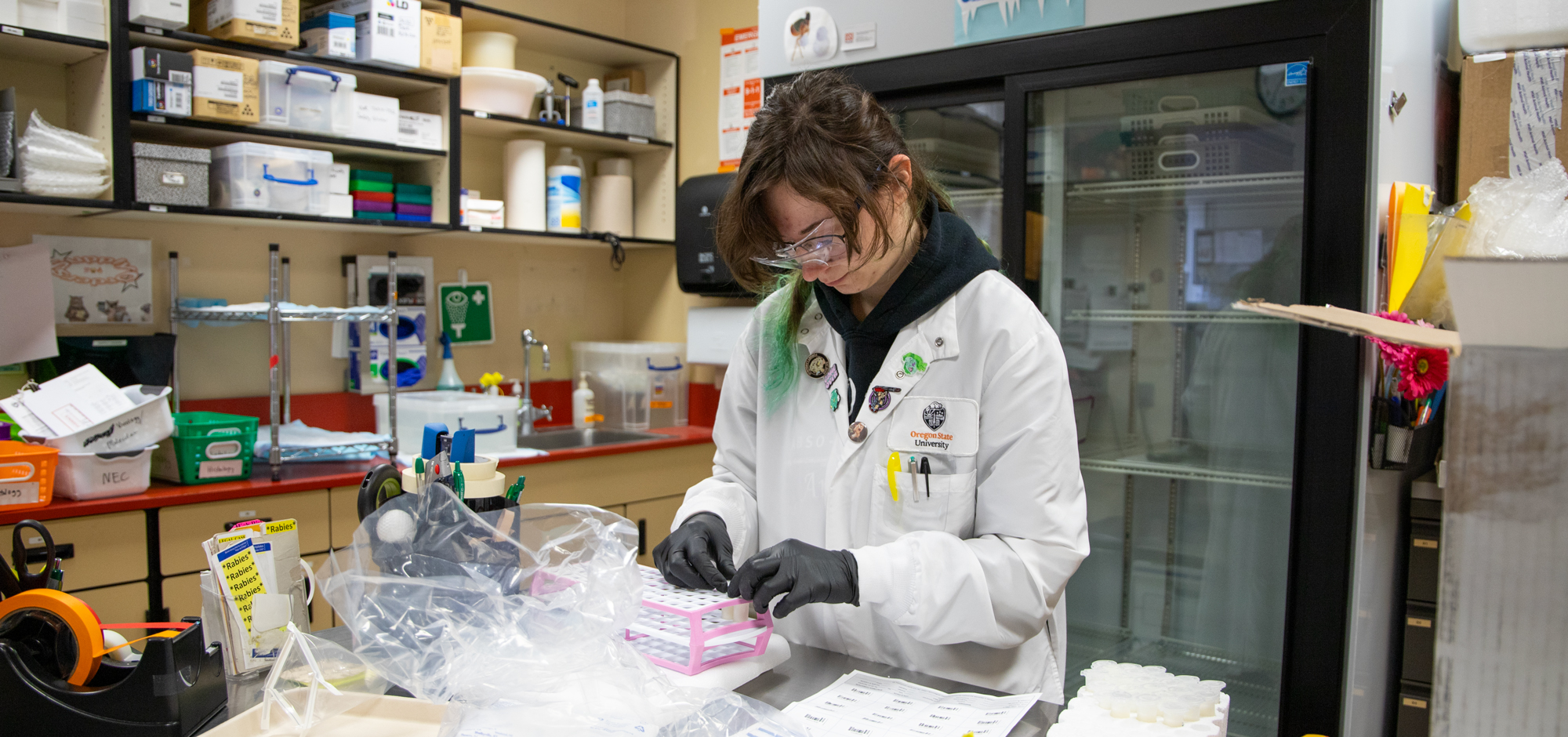

Caitlin Van Meter, medical technician, prepares milk samples for HPAI testing at the OVDL's Receiving Department.

February 22, 2025

Words by Dr. Kurt Williams. Photo by Jens Odegaard.

Testing for highly pathogenic avian influenza has been ongoing at the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory for nearly three years, with no end in sight.

Before HPAI came on the scene, the OVDL was one of Oregon’s lead laboratories in the COVID-19 pandemic, testing more than 300,000 human samples for the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus. So, they have experience handling the practicalities of high-capacity testing.

The first positive HPAI case in Oregon in the current outbreak popped up in a dead goose from Linn County in early Spring 2022. Since then, the virus has expanded across the state and nation, impacting poultry production, killing untold numbers of wild birds and jumping into a diverse array of mammals, including dairy cattle and humans.

As Oregon’s sole member of the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Animal Health Laboratory Network or NAHLN, the OVDL is the only laboratory in Oregon approved to test animals for HPAI. As of the end of January 2025, the laboratory has run approximately 35,000 tests for influenza virus since the onset of the outbreak in 2022.

Testing plays an important role in efforts to get the virus under control. It’s important not only to know if a sample is positive or negative. What species was tested and the geographic location where the sample originated are also important. This information allows scientists to track the spread of the virus, what species and sectors of the economy it’s impacting and how the virus may be evolving.

Inside the Lab

To understand how a sample goes from arriving at the OVDL for HPAI testing, to test results being reported out is to appreciate the inner workings of the laboratory, the import of this work and why one can have confidence in results received from the laboratory.

Testing for HPAI is laborious, precise and done with urgency. People’s livelihoods can be at stake, depending on the test results. All samples arriving at the OVDL for HPAI testing – whether dropped off by an individual animal owner, representatives of the Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA), the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) or by overnight delivery service – comes first to the laboratory’s Receiving Department.

It’s not uncommon for upwards of 200 samples to arrive at the laboratory for HPAI testing in a single day. Before testing can commence, there’s work to be done in Receiving. The submitted sample is compared with the submission form to verify it’s the correct sample and its identity matches what the submitter claims it is.

Once the chain of custody is verified, the sample is entered into the laboratory information management system (LIMS) and barcoded with a unique accession number linked back to the owner or submitter, the location the sample was taken and the species it came from.

Though HPAI has been in the United States for years now, and doesn’t appear to be leaving anytime soon, if it’s diagnosed in domestic poultry it's designated as a foreign animal disease or FAD. For this reason, HPAI samples from poultry are assigned an FAD number for use by the ODA and USDA.

Once receiving’s ducks are in a row (pun intended), samples for HPAI testing are transferred to the OVDL’s Molecular Diagnostics section.

Because of the virus’s expanding impact on animals, samples for testing could be a swab from a chicken, milk from an Oregon dairy, lung from a dead seal at the coast or a piece of brain from a cat with neurologic disease.

But how does one go about finding the virus in all this stuff?

RNA ID

First step: separate the wheat from the chaff. HPAI is an RNA virus. RNA is wheat, and everything else is chaff. After the RNA has been extracted from the sample, identifying HPAI-specific RNA amongst all the other RNA conjures a different metaphor: finding a needle in a haystack. To do this, OVDL scientists rely on the polymerase chain reaction or PCR, the same technique we all became painfully aware of during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It takes more than one PCR test to detect HPAI. The first test isn’t looking for HPAI specifically; it’s looking for the virus’ family. HPAI is an influenza A virus, related to other flu viruses like seasonal flu in people and a host of similar viruses in other animals, including waterfowl where HPAI first emerged.

So, the first PCR test looks for evidence of influenza matrix gene, present in all flu A viruses. If this test is negative, it’s concluded there’s no influenza A viruses and testing stops.

If the matrix PCR is positive, testing continues, looking for more specific evidence of HPAI’s presence. Perhaps you’ve heard HPAI referred to by another name: H5N1. Though the name wouldn’t be out of place in a Star Wars film (think R2-D2) it’s actually a reference to two influenza viral proteins: hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminadase (N).

H5 and H7 influenza viruses are problematic when it comes to causing disease in humans and other animals. Therefore matrix-positive samples are next PCR tested for the presence of the H5 gene. If it’s negative, testing for HPAI is over, though the sample may undergo an additional test for H7 depending on the circumstances.

Matrix-positive, H5-positive samples undergo one final PCR test, to pin down the diagnosis of HPAI, the so-called H5 2.3.4.4.b test, which is considered confirmatory for HPAI.

Alerting Authorities

“DETECTED” samples trigger a flurry of communication to state and federal partners. Depending on the sample origin, this may mean a phone call or email to the state veterinarian, the NAHLN, the federal diagnostic virology laboratory at the USDA or the ODFW for samples from wildlife. Lastly, the results are communicated to the USDA Emergency Management System from the OVDL’s laboratory information management system using a digital messaging system.

The laboratory has two business days to get HPAI testing completed after the sample arrives at the OVDL. Once testing is completed, an electronic message with the result must be sent to the National Veterinary Services Laboratory at the USDA within 24 hours.

It’s not uncommon for results to be released the same day samples arrive at the laboratory. If necessary, people work into the evening to turn samples around quickly for high priority, high stakes cases, such as commercial poultry operations the ODA is working on in the state.

This detailed protocol has happened tens of thousands of times in the OVDL over the last three years, and will continue. Every step of the process is backed up by oversight established in the laboratory through its quality assurance program, reams of standard operating procedures and regular proficiency testing for the scientists performing the work.

The OVDL has a many decades long history as a valued partner in Oregon’s animal and public health infrastructure. Its efforts to combat HPAI in the state and nation is its latest contribution in this effort.